Sometimes a relationship doesn’t vibe.

Other times, challenging relationships can provide the most fertile ground for growth.

As the lead mentor for new teacher induction in Miami-Dade Public Schools, Cheryl Pickney has seen relationships that run the gamut – from best friends to friction that feels like it hangs in the air. But one particular relationship stands out.

“We had a music teacher mentoring an art teacher,” said Cheryl. At first, the art teacher was very withdrawn. “It was like pulling teeth to get him to come to mentoring sessions,” she said. He didn’t seem to see the value in mentoring, and just wanted to be left alone. Then the relationship with his mentor went from cool to icy.

“At one point during an observation with his support mentor, he literally got up and headed to the door saying ‘I don’t trust this, I’m out of here,’” said Cheryl. Luckily, Cheryl was also there and able to work side-by-side with the mentor to deconstruct the barriers to building trust in their relationship. They talked about what made him uncomfortable. But he was reluctant to continue mentoring, and just didn’t think it was a good fit.

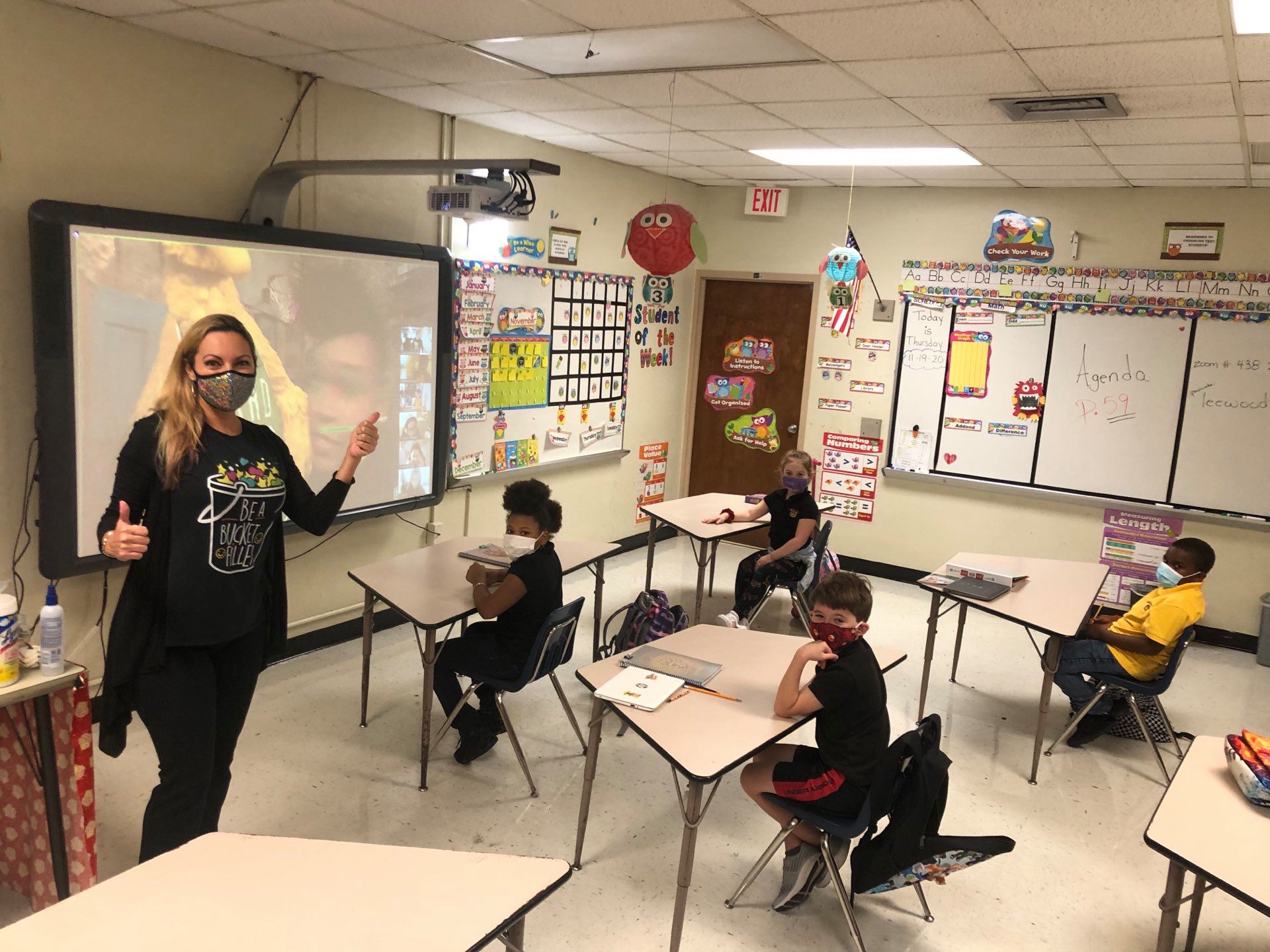

Teacher in Miami-Dade working with students during COVID-19 pandemic

Something had to be done.

Cheryl sat down with the mentor and looked at the script from the conversation. It became very clear what the art teacher was experiencing in sessions. “I realized [the mentor] was just rolling through the questions without really listening,” said Cheryl.

Cheryl worked with the mentor to focus on intentional listening as a way to repair and rebuild the relationship. “I told her, ‘Next time, do away with the script and really listen to what he says.’”

Successful coaching and mentoring isn’t ticking off a checklist. Attending to the needs of teachers and following paths — even when deviating from the topic at hand — deepens a sense of partnership.

And it transitions power from a place of imbalance where one dictates to the other, to a collaborative and co-creative space that allows for autonomy and strength of voice. “If you’re intentional in your listening, you can reach him,” said Cheryl. “We started making a plan.”

The practice of coaching hinges on the fact that feedback is critical for growth. But being open to feedback requires tremendous groundwork – groundwork that involves deep listening and connection, and a willingness to be adaptive. The mentor Cheryl was working with needed to lay the right foundation for feedback to be received and take root.

Starting over, the mentor and the art teacher began building common connections as people, finding grounds to share that exist outside of a space of judgement and critical feedback. Their conversations became more open, more personal. Turns out, he’s a musician himself and in a band. “It was something he didn’t really share with his students or the staff. But she talked with him about it,” said Cheryl. Little by little, they made a connection.

Group of students working on a biology project

She mentored him for the next year and Cheryl is happy to report “you could see the growth.” By the end of the year, he was really opening up — not just with his mentor, but with his students as well.

He even performed at the year-end assembly. “His students, they weren’t ready for that,” laughed Cheryl. When he got up on that stage and started to perform, “they were shocked to see that he was this really cool guy.” He began to establish real connections with his kids – the kind of relationships that reach beyond the curriculum. Those sorts of classroom connections are invaluable, and can lead to better, deeper learning and engagement.

Cheryl credits this transformation to his mentor. “Her work with him helped change the connection he had with those kids.”